The agent at the desk was a gruff short-haired woman who managed to be as welcoming as one would expect, but no more than that. She informed me that I could touch anything in the museum. It was meant to be interactive.

The sign confirmed this, but basically also said “please don’t break things.”

So I entered the Museum of Memories of Communism feeling curious and open minded. I found a piano and tapped the keys. The first key didn’t work and the others produced sounds that were tinny, discordant, and strange. It clearly hadn’t been tuned since the Revolution.

The woman quickly appeared and wordlessly closed the cover to the piano, smiling at me. Apparently I was permitted to touch almost anything.

The visit to the museum had been a lark of a way to pass some time this afternoon, but it was really a lot of fun. The nicknacks were mildly engaging, but the stories scattered about on the walls were the highlight.

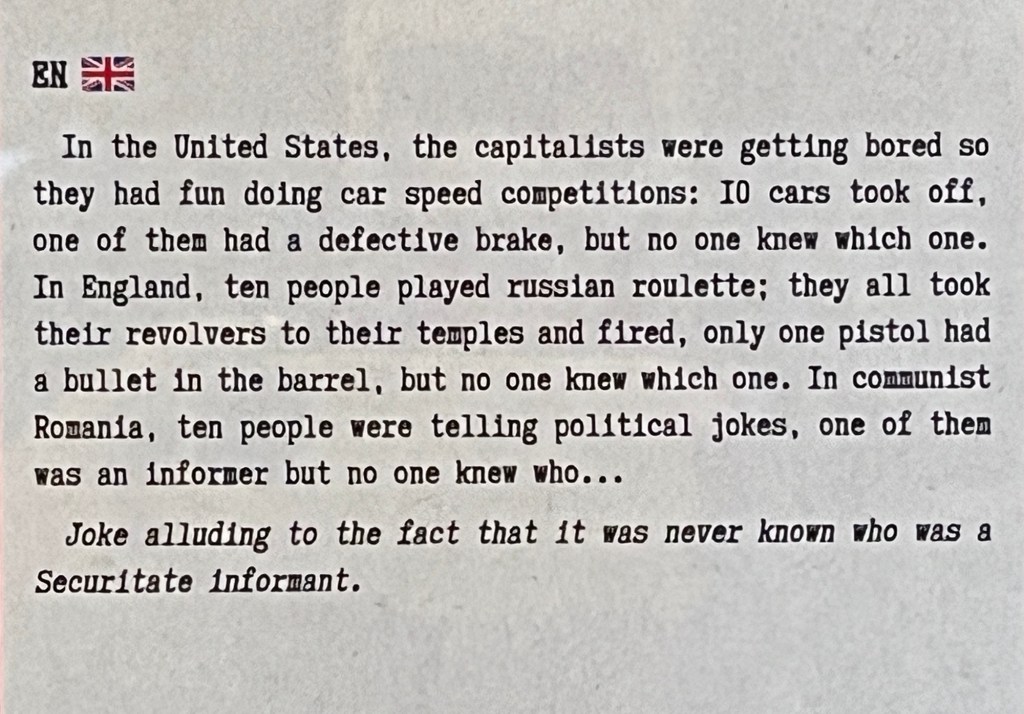

This joke was funny, in it’s way.

And this giant fiberglass submersible somebody was making was accompanied by an engaging tale of a plan for escape that was moving, enthralling, and ultimately unneeded when communism fell.

This was a good ending to the afternoon, and a bookend to pair with a morning that had been spent on a tour of the Bran Castle, about a half hour from town.

Two of us were on the tour, and our guide, Charlie, picked us up while the town was still quiet. He drove us there, telling stories of the history of the area as we went. As guides often do he rushed to get us inside, ostensibly to beat the crowds, but nothing is especially crowded when I travel (this is the off season, after all), so I suspect they just want to get it over with.

Charlie wasn’t impatient however, and he regaled us with stories surrounding the history of the castle, which was built in 1377 by the Saxons on a rocky hillside at the border between the provinces of Walachia and Transylvania, when Transylvania was part of Austro Hungarian Empire. It was built to guard the Empire against invading forces, such as Ottomans, who might come from the south.

Bram Stoker, who wrote Dracula, had never been here but had read some of the stories of the region and knew about Vlad the Impaler. He used that information he had gleaned to craft his own tales. It’s not clear that Stoker even knew about this specific castle, although some elements match the description. Therefore it’s not clear that this was, in fact “Dracula’s Castle,” and even if it was, the truth is that Vlad the Impaler was never here.

The castle tour really exceeded my expectations. I had worried that the displays would be way overdone with the vampire angle and it would be a big haunted house, but most of the castle’s displays were dedicated instead to the history of the structure, the royal family, and the region. One of the higher floors had some displays focused on local mythical monsters, with one room dedicated Dracula movies (BTVS made the list!), but that was the extent of it.

Together with Charlie’s narrative I learned a lot, and I think the biggest take-home is that Vlad the Impaler wasn’t the stuff of nightmares for the locals. He was a Wallachian prince who had been raised in the Ottoman Empire, where he learned the tactics of the Ottomans. When he returned home, the Ottomans expected his alliance, but instead he used the knowledge he had gained to defend his homeland.

His title was earned by his habit of impaling invading troops on massive spikes and posting them as a deterrence, ideally while still marginally alive. This was admittedly brutal, but it is what one does.

As it turns out, even to this day, Vlad the Impaler isn’t viewed as a monster, and is instead viewed as a hero locally.

As we moved through the displays we learned that Romania only briefly had a royal family (6 kings), who were deposed by the communists. During the period of the monarchy this castle became a home to the last Queen, Marie.

The story of her youngest and favorite daughter, Ileana, is another tale that remains with me. She ran a hospital in the castle during the war, and was exiled when the communists rose to power. Later she became a nun and moved to Pennsylvania where she founded a monastery. After the fall of communism she came back to her beloved homeland for a visit, taking a handful of Romanian soil home to Pennsylvania with her, to be buried with her when she eventually passed away a few years later.

And while the story gave me all the feels, I couldn’t help but wonder, “how did she get the soil back through customs?”