I stepped into the Old Jewish Cemetery next to the cafe and immediately the air seemed to grow heavier, the shadows deeper, the temperature cooler, and the grass longer.

I walked slowly up the path into the dense shade and noted the numerous small stones placed on the gravemarkers, indicating that the deceased was honored and remembered (there are several reasons cited for the placement of stones – this is just one of them). Some of the few graves I saw were 150 years old, and I wondered at how long those stones had been there and who remembered them. The stones looked new.

It was no matter. This was a cemetery, and a Jewish one at that. Too often these are places that have been defiled by outsiders. I wanted to be respectful and decided that maybe this wasn’t where I belonged, so I turned around.

The cemetery wasn’t my first interaction with a necropolis today. I had started the morning with a trip to the Archeology Museum of Split, which stands about 3/4 of a mile outside the walls of Diocletian’s Palace.

The interior of the museum is currently entirely dedicated to a temporary exhibit featuring the necropolis at Solona, an Ancient Roman city that once stood just west of Split.

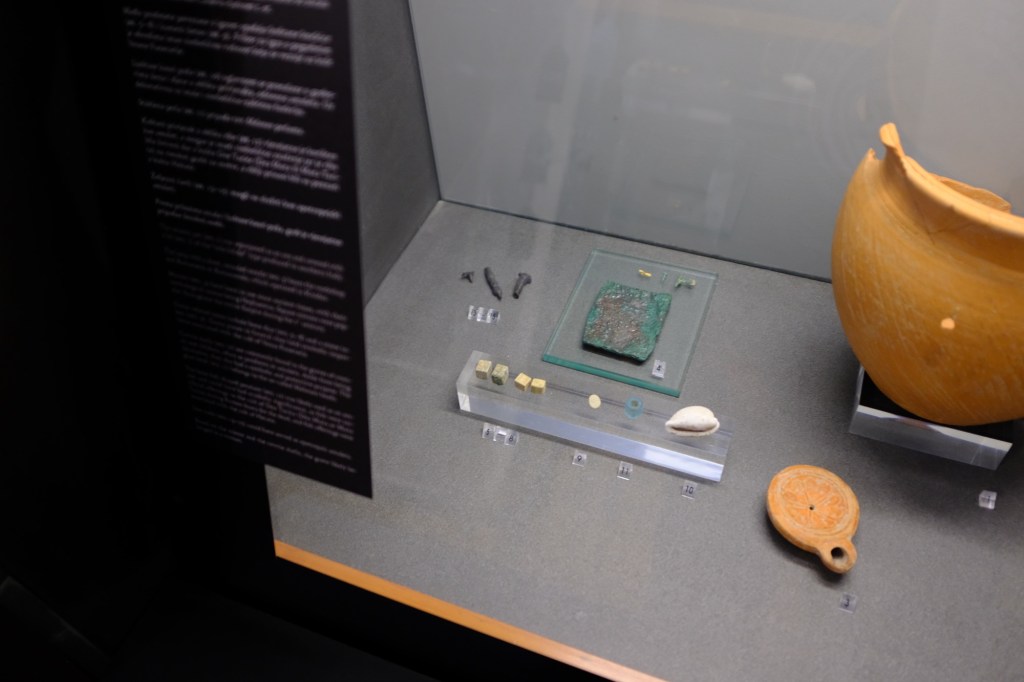

On display are the contents of the various graves excavated from the necropolis: little trinkets and memories left behind to accompany the deceased to the next world. Such as these dice. Something impresses me about the six-sided die and its universality.

They have a lot of blown glass in the cases. They explain that glass blowing was very important in the Roman Empire. In fact almost all of the glass they have on display here is blown.

This glass boat, however, is an exception. It wasn’t blown glass – it was molded.

Although it was an interesting exhibit, it was more distracting than engaging because of the curation. I’m not questioning keeping the contents of a given grave together (this is basic). Instead I take issue with the large passages of text explaining what we should be looking for. Sometimes they would refer to an item (such as the glass boat) and not tell us where to find it. Or they would refer to a grave number that was somewhere on the other side of the room. In the end I spent a lot of time walking back and forth trying to remember numbers and recall what I was looking for.

Outside, the museum has a large lapidarium. What I’ve found is that any museum dedicated to ancient history in this part of the world has one of these. They have a bunch of big pieces of marble that are nice, but not that special, and they take up a lot of space. So the museum just puts them together in an overcrowded room (if they’re lucky) or outside somewhere.

Typically, there is perfunctory signage, but not much more than that. A visit to the lapidarium can be overwhelming, and I’m sure the task of trying to make it into something sensible is overwhelming for the museum as well.

Still, there are gems to be found, like this piece of flooring – it’s pretty remarkable, and I’m surprised that ie ended up outside. But then again, I have a thing for ancient floors and mosaics.

It was after my visit to the museum that I visited the cemetery. I was on my way to the top of Marjan Hill.

Marjan Hill is called the “lungs” of the city, a big green park on a peninsula adjacent to Split. At its peak, the view of the surrounding sea, islands, and cities is spectacular, and the breeze that touched me was refreshing.

After taking a break to rest my feet and enjoy the view, I turned around and headed back to town and lunch.

On my way back I passed once more by the Jewish Cemetery. I considered venturing back in, but again decided against it.

I’ve had enough of cemeteries lately.