It’s impossible for most of us to really know the history of the world. I’ve come to accept that over the years, but it always makes me feel a little bit bad.

In school I was taught a version of history that begins in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt and courses through Ancient Greece and Rome. It continued through Medieval Europe, moving through the crossing of the Atlantic briefly by the Vikings and later by Christopher Columbus. This is a story that isn’t fundamentally wrong, but it’s also incomplete.

The fact that there was some history taking place in Asia was mentioned briefly, but it was very limited in scope and didn’t interest me much at the time. I was much more interested in the temples and columns of Athens than the walls in China.

As I consider it, unless one is specialized, perhaps much of history is local. While we learned some European history in school, it wasn’t in nearly the same detail we applied to American history. And I’d imagine Korean schoolchildren don’t spend much time, if any, on the US presidents.

I thought about this as I stood in the Korean War Memorial, reading about the thousands of years of war that have scarred this small peninsula. And I considered the somewhat morbid notion that the history of humanity is dominated by the history of war. There are probably hundreds, if not thousands, of wars that other people learn about that have never affected us.

In any event, this was a day of Korean History.

I began at Gyeongbokgung Palace. This was the first Royal Palace of the Joseon dynasty, who ruled Korea for 500 years. The original structure here dates back to 1395 and has been alternately burned down and rebuilt across the centuries. In the early 20th century it was systematically destroyed (including dismantling and selling parts) by Japanese colonists in an attempt to erase the autonomy represented by the structure. The buildings standing today are a reconstruction that began in the 1980s.

I listened as the audoguide listed names that really meant nothing to me, feeling vaguely guilty about not knowing these people and struggling to process who they are. But I also considered that a long list of European monarchs wouldn’t fare much better, even if the names had a certain familiarity. I really don’t know the difference between Henry III and Louis XIII.

So maybe it’s enough to know that this was the king’s bedchamber, and that’s why it doesn’t have a large beam running from left to right across the top. (That beam would represent a dragon, or king, and a building can’t have two kings.)

And it brought me joy to visit King Gojong’s study, still maintained as a small public library. Places like this matter, even if they don’t have personal memories.

And it’s breathtakingly incredible to know that this is the building where the Korean alphabet was devised. They take pride in that — it was clear just listening to the story on the audioguide. Until they had their own alphabet, the Korean people relied on Chinese characters, and having their own letters established them as being truly independent.

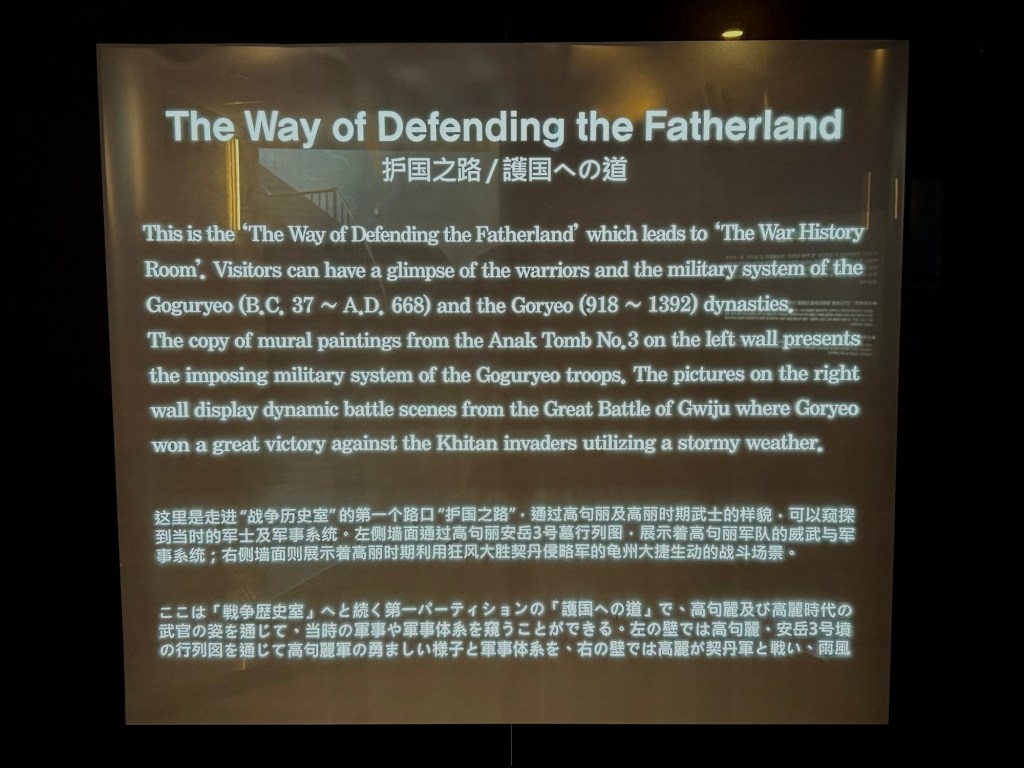

It was with these snippet of history in my brain that I walked into the Korean War Memorial in the afternoon and read the timeline of wars that have shaped this land. Wars that predated the unification this country under the Silla dynasty in 668 AD, and wars that divided it.

I had expected the Memorial to be a mournful display, focusing on the war between South and North Korea, and much of it does, but there is more here.

Ancient history is on display here as well, with prehistoric stones, shaped by early human hands 500,000 years ago.

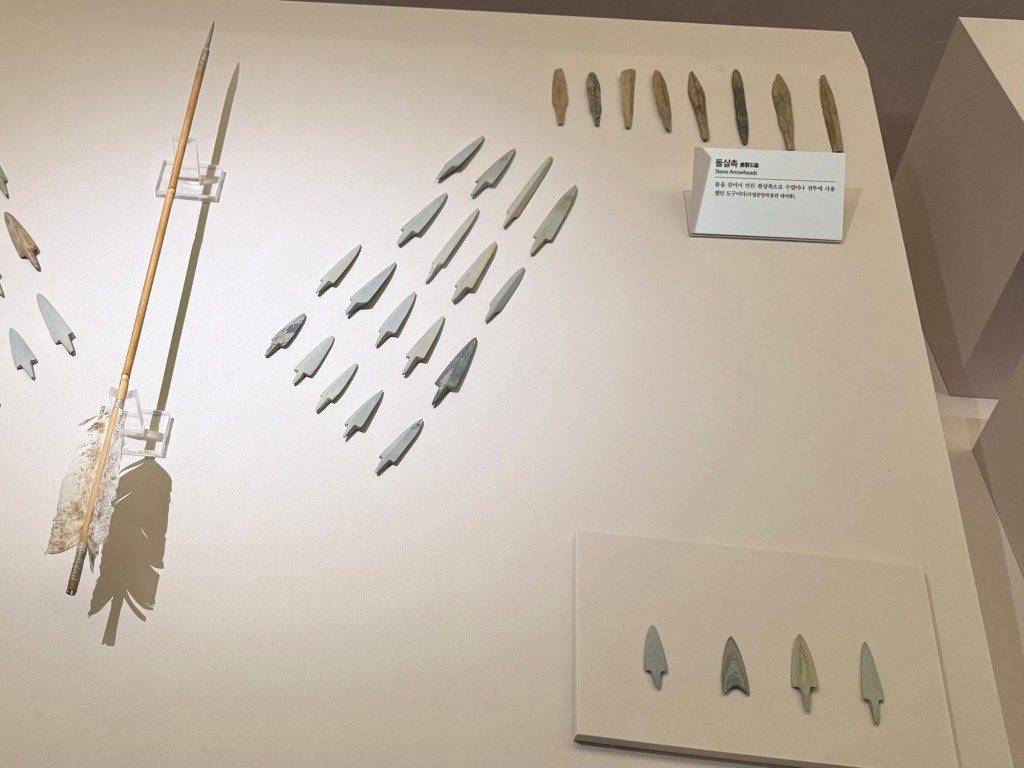

And stone arrowheads, crafted with a precision I don’t think I’ve ever seen before.

So while they have examples the machinery that dominated this country in the 1950’s, they have much more – millennia of war stories and gear.

And while they have displays memorializing the dead, as I walked into the garden where children were playing amongst giant planes and artillery, I considered that this is a memorial that both mourns war, but also seems to celebrate it.

And I thought of the context of all that I had seen today and the stories I had heard. I thought about Koreans fighting again and again for their independence. And I contemplated the importance they placed on establishing their own alphabet.

These were all things they had to do to protect themselves, so I guess it might be understandable that they celebrate them.

And I also thought about how much of the history I have been taught over the years focuses on the wars. Which means Korea isn’t unique in this.

And I still don’t know how I feel about that.